Sylvester Guzzolini And His Congregation

Presentation

The Conciliar Decree Perfectae Caritatis reminds us that « The appropriate renewal of religious life involves two simultaneous processes: a continuous return to the sources of all Christian life and to the original inspiration behind a given community, and an adjustment of the community to the changed conditions of times » (n. 2).

Our Declaration, with the intent of promoting such a renewal, explicitly refers to the past history of the Congregation, indicating how it should be approached. A genuine renewal is neither return to obsolete ways of life nor development totally eradicated from tradition. We must receive with « a grateful heart » whatever positive values « our Fathers » have handed down to us, while, at the same time, we ought to remain open to the impulses of the Holy Spirit, who operates now, as He did then, in the Church.

Ours is a long history stretching over seven centuries. We, however, know it very little, since we do not yet have a good, critical and complete study on it. The lack of material for a study of our history is particularly felt in our English-speaking communities by those in charge of formation.

There have been along the centuries monks who have made careful research into our history. The precious writings of the Ven. Andrew first and of Moronti and Feliziani later, have been our « traditional » sources of information. Other more recent authors, like Franceschini and Bokonett, who dealt mostly with particular topics, drew almost exclusively from them. The one who opened the way to a more ample and organic study of our history was D. Anthony Cancellieri with his work Brevi cenni storici intorno alla Congregazione Benedettina Silvestrina (Brief historical notes regarding the Benedictine Sylvestrine Congregation). It was published in 1935 « ad uso privato dei Monaci Silvestrini » (for private use of the Sylvestrine monks), and was specially intended for the « young, who would not know where to turn for a knowledge of our past ».

From that time onward, as if in answer to D. Cancellieri’s wish, there has been a flourishing of historical studies. Research has been undertaken into our original documents, both those preserved in our archives and those, until now unknown, preserved in others, first among them the Vatican Secret Archives. Our magazine « Inter Fratres », which was begun in 1950, has been a strong incentive for research and study and a valid medium for publishing the results.

Particular mention should be made of D. Pius Federici, Abbot General from 1966 to 1972, who ordered a new biography of the founder to be written, suggested and encouraged five new doctoral theses on the origins, spirituality and other historical subjects regarding the Congregation.

The Monastery of Montefano is now, as it has been in the past, the centre of this flourishing of study and research into our history, thus fulfilling its function of « head and mother of the Order » also in this field. Various high level historical seminars and meetings have been organized, and the valuable collection of « Bibliotheca Montifani » started, all of which entailing considerable financial layout.

Although much has been done, it is still too early to plan a complete history of the Congregation. Something, however, I had visualized for some time as possible, vz. a publication which would order in some historical sequence the results of the studies and research made up to now. This has been undertaken and brought to completion very competently by D. Hugo Paoli, who has done already a tremendous amount of work in the field of research into our history. The work, which is published in a special number of « Inter Fratres » in Italian and in English, is destined mainly to the monks of our Congregation. Hence the author has purposedly limited his use of source material to what is available in all our monasteries, as published in « Inter Fratres » and in other Sylvestrine editions. The continuous use of this material is also intended to make one more familiar with it and be an incentive to pursue studies and research in various fields still unexplored of our history and to commit to writing, lest they be forgotten, more recent events.

My, and I am sure that I can add our, sincerest thanks to D. Hugo for his work. We all hope that he, already an « expert », will continue his research and study, so that a better and deeper knowledge of our heritage may become a source of inspiration for us today.

SIMON TONN, OSB. Silv, Abbot General

Rome, Monastery of S. Stefano Protomartire

31 December 1986

Sylvester Guzzolini

Sylvester Guzzolini was the founder of the Sylvestrine Congregation of Benedictines. He was born at Osimo (province of Ancona, Italy) in the Marche, about 1177, and died in the monastery of Montefano near Fabriano on 26 November 1267.

I. Sources

In reconstructing the life and spiritual journey of Sylvester Guzzolini we have two types of sources, archival and literary.

The first consist of contemporary documents directly concerning the Saint himself or persons and institutions which had with him close relations. They are essentially notarized deeds, dated from 1231 to 1267, most of which are preserved in the historical archives of the Congregation, kept in St. Sylvester’s monastery of Montefano, near Fabriano (1). These sources, while containing little information, are nevertheless fundamental in reconstructing the life and work of the founder, for they establish with certainty some chronological data.

The literary sources, which according to rules of Medieval hagiography frame the events in a theological-spiritual perspective, include: the Vita Silvestri (Life of Sylvester), written between 1274 and 1282 (with later additions) by Andrew of James from Fabriano, who became the fourth Prior General of the Congregation (1298-1325): he draws his information from eye-witnesses and, perhaps from his personal knowledge of the founder the Vita Hugonis (Life of Hugo) and the Vita Johannis a Baculo (Life of John of the Staff), disciples of Sylvester: both Lives are by the same author Andrew of James and written at the beginning of the XIV century; the vita Bonfilii (Life of Bonfil), monk, bishop and hermit: the Life is attributed to the founder himself and assumes, therefore, the character of a quasi autobiographical document (2).

Complementary material is to be found in later hagiographical narratives, especially in the Breve Cronica della Congregatione de’ monaci Silvestrini dell’Ordine di S. Benedetto, dove si contiene la vita di S. Silvestro abbate, fondatore di detta Congregatione e d’alcuni altri beati suoi discepoli (Brief Chronicle of the Congregation of Sylvestrine monks of the order of St. Benedict, containing the Lives of St. Sylvester Abbot the founder of the said Congregation, and some of his Blessed disciples), by Sebastian Fabrini (edited at Camerino in 1613, with a 2nd edition, Rome 1706). The contents of this work are valuable, however, only in so far they hand down data which had been lost or help in interpreting the sources more accurately.

Amongst Fabrini’s personal notes, not supported, however, by documentary evidence is that of Sylvester being priest: « Sylvester was elected and promoted to the dignity of Canon in the cathedral church of the city of Osimo. Seeing himself elevated to such a high status, he did not allow himself be swayed by the spirit of pride or vainglory, but, more than ever intent on the divine service, with the greatest humility and devotion, having attained through all the other grades to the dignity of priesthood, gave himself fully to the practice of holy contemplation and prayer and to all the good work which went with his status » (p. 5) (3)

II. Life

Until 1231, the first certain date in the life of the Saint, the other biographical data are taken from the Life of Sylvester: most of them are furnished to Andrew of James by the bishop of Osimo Benvenuto Scotivoli (1264-1282), a fellow-student of Guzzolini.

a. Canon

Sylvester was born in Osimo in the Marca of Ancona about 1177. Since his biographer affirms that at his death, which occurred on 26 November 1267, he was « almost a nonagenarian » (Life ch. 37), 1177 is conventionally accepted as the year of the birth the founder. His father Gislerio, of the noble Guzzolini family, of strong Ghibelline tradition, sent Sylvester to study law at Bologna and Padua. After a short period Sylvester abandoned the legal studies to dedicate himself to Theology and Sacred Scripture (4). This caused a deep rift with his father.

On his return to his home town, however, he was made Canon of the cathedral church of the city (5) (Life, ch. 1).

He conscientiously undertook his office, dedicating himself « to prayer and preaching » (Life, ch. 1). He often had to reproach his bishop, who sought every pretext to deprive him of his canonical benefice. The Life does not mention the name of the prelate. It is certain, however, that he was Sinibald I, who governed the Diocese of Osimo from 1218 until 1239. The contrasts between the bishop and Sylvester had probably political motivations, as well. Sinibald in fact « was a very resolute man of arms and of government, who strongly supported the Guelphs and persecuted the Ghibellines », to whom the noble imperial family of the Guzzolini belonged (6).

In the midst of all this an incident occurred which made Sylvester take a decision about his future. One day, at the conclusion of the exequies for a dead person, when the Canons lifted the tombstone of the common grave, they found the corpse of one Sylvester’s relatives not yet reduced to dust. This person had been known for his good looks and had died very young. This pitiful sight deeply moved Sylvester, who resolved to « change his life for the better ». « As he was returning to his room », writes his biographer, « the scriptural text came to his mind, which says: ‘Whoever wishes to follow me, must deny himself, take up his cross and follow me.’ And he understood that it was addressed right to himself ». (Life, ch. 2).

b. Hermit

About 1277 Sylvester left Osimo and retired to a life of solitude among the crags of the « Gola della Rossa » near Serra S. Quirico (province of Ancona – Italy), in the territory of Count Corrado, Lord of the castle of Rovellone. The Count, among other things, had already known Sylvester in the Curia of the Legate for the Marche, where the latter had been involved in the defence of the rights of the church of Osimo.

Sylvester lived in three different caves, the third of which can be definitely identified as Grottafucile, where subsequently a monastery was built, dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary (7).

The oldest title attributed to the Guzzolini is that of « Prior of Grottafucile Hermitage » (8). At Grottafucile Sylvester led a life of severe penance and constant prayer, having only raw-herbs for his food, as he later revealed to his disciples.

Sylvester, however, did not remain unknown for very long in this solitude. He was visited by members of various religious communities, who admiring him for his virtues, tried to persuade him to join their order. The hermit « began » then « to think about the form of religious life he should embrace » (Life, ch. 4). After mature reflection he chose the Rule of St. Benedict of Norcia, one of the rules canonically approved before the Fourth Lateran Council (1215), which, in the constitution 13, prescribed that new foundations had to adopt the Rule of an already established « Order » (9).

Sylvester received the monastic habit from the monk Peter Magone. The Life, however, does not specify when and where this occurred: probably in one of the numerous abbeys of the area.

c. Founder

In 1228 two Domenican religious, Riccardo and Bonaparte, sent by Pope Gregory IX to « visit the clerics of the Marca », exhorted Sylvester « not to end his days alone in that solitary to place » (Life, ch. 5). The Guzzolini accepted their suggestion and received at Grottafucile his first disciple, Philip from Recanati, directed to him by the above mentioned Visitors (10).

Others wishing to embrace the anachoretic ideal followed the example of Philip and placed themselves under the spiritual guidance of Sylvester, who little by little built other monasteries, preferring for them « solitary places » (Life, ch. 6).

In 1231 Sylvester founded the hermitage of Montefano on an area of 2,640 sqm. donated by six citizens of Fabriano with four distinct notarized deeds (11). The monastery is about 5 Km (3,1/2 miles) from Fabriano, at 800 m. above sea level, close to the summit of Montefano, a part of the Appennino Umbro-Marchigiano, in a picturesque and panoramic position (12).

The hermitage, which was completed in 1234, was dedicated to St. Benedict and soon became the centre of diffusion of the order. The present day title of « St. Sylvester » was given to it about the middle of the 16th century (13).

Other foundations followed: that of St. Mark of Ripalta, near Rocca Contrada (today Arcevia, in the province of Ancona) and of St. Bonfil near Cingoli (province of Macerata) (14).

The year 1244 saw the beginning of a monastic nucleus in Fabriano with the donation by the « Commune » (city council) to « Fra Silvestro » of 176 sqm. of land near Borgo Nuovo. A house with an oratory was built on the site, and it served, till the death of the founder, exclusively as a residence for the monks who from Montefano came down to the city (15).

On 27 June 1248 the new religious family obtained canonical recognition from Pope Innocent IV under the title of « Order of S. Benedict of Montefano » (16).

Subsequently the Guzzolini built the monasteries of St. Bartolo della Castagna, near Serra San Quirico, St. Pietro del Monte, near Osimo, St. Marck and Lucy of Sambuco (province of Perugia), St. Thomas of Jesi, St. Bartolo of Rocca Contrada, today Arcevia), St. James in Settimiano of Rome, St. Benedict of Perugia and St. John of Sassoferrato.

Sylvester’s communities were generally of modest proportions and not well endowed. The monks, for the most part were who not ordained priests, gave themselves the fields to working and to begging.

At the death of the founder, which occurred at Montefano on 26 November 1267, situated in the Marche, monasteries, in Umbria and Lazio, were 12, and the monks about 120 (17).

The mortal remains of the founder were laid in a cypress coffin that was placed in the church at Montefano. (18). In 1532 the tomb was placed above the main altar by the Prior General Anthony Favorino: in 1629 it was transferred to a niche in the apse; in 1660, to avoid damage by humidity, the sacred remains of the Saint were enclosed in a marble urn, which again was once placed above the main altar. Finally in 1968 this sarcophagus was replaced by the present one of brass and crystal which stands now under the main altar (19).

III. Sprituality

Sylvester, man of the Spirit, did not, as also other monastic founders, translate into juridical formulae his own charismatic intuition: he was above all witness, inspirer and guide to his movement. The hagiographical documents evidence the role that Sylvester had at the beginnings of the order of Montefano as « spiritual father, very attentive in ruling the brothers » (Life, ch. 6) (20).

Sylvester’s experience as that of St. Benedict was initially hermitical, on the model of the Fathers of the Desert (21). It is presented as a re-reading of the Benedictine tradition in the religious and socio-cultural context of the Marche in the 13th century (22).

Sylvester knew how to read the ‘signs of the times’ and how to grasp the innovative ferments of his epoch, while local monasticism remained anchored to a feudal system already out-of-date. The abbeys in the Marche, including Fonte Avellana, because of their wealth, number of dependant churches and the authority of their abbots, exercised in the 13th century more political and economic influence than spiritual impact (23).

The Guzzolini, undoubtedly influenced by the Franciscan phenomenon (in 1234 he was present at the foundation of the first convent of Franciscans in Fabriano) (24), reaffirms the values of monastic life, giving them new forms, which answered the exigencies of the medieval society. He impressed on his Order a marked note of poverty, introducing the practice of begging and proposing to his community a life style poor, simple and austere, in line with the « innovatory spirit » of the 13th century.

In the two deeds, with which the citizens of Fabriano in 1231 donated to Sylvester the land on Montefano to build a hermitage near Fonte Vembrici a spring which still monks exists – the « monks of the Order of Fra (Brother) Silvestro » are spoken of as leading a « life of penance and solitude » (25).

From the Life we learn, besides, that disciples of Sylvester wore a « rough habit and at table did not know « variety of food, nor did they eat refined or palatable dishes, but practiced constant fasting » (Life, ch. 6).

The choice of the title of Prior instead of Abbot speaks of a precise option on the part of the Canon of Osimo regarding his life style, for Abbot in medieval times was synonymous with power and prestige (26).

From the recognition of the relics carried out on 11 July 1968, Sylvester appears to have been of small stature (1. 60m) and slight of build. (The Life speaks of corpusculum small body ch. 6). He was of angelic countenance, refined in manners, ardent with love towards his sons, and the devout persons, compassionate visitor of the sick, consoler of the afflicted ». According to his biographer, Sylvester is the « Man of God », a protagonist of a magnificent ascent in faith and virtue (Life, ch. 6).

Intense was also his mystical experience: the vision of Christ’s tomb (Life, ch. 28) and of the communion by the hands of the Blessed Virgin Mother (Life, ch. 29) were for Sylvester the culmination of his communion with God. Growth in love for the Passion of Our Lord, a very special understanding of the Scriptures, the power of miracles and the gift of prophecy followed from these experiences. « The Man of God » arrived thus to the fullness of his charismatic life, sealed by his death, the « last sublime impetus of the spirit longing for communion with God » (27).

IV. Cult

The cult of Sylvester was born of his « fame of sanctity » at popular level and fed by the miracle working of the « Man of God » (this attribute occurs 52 times in the Life). Already in 1272 (only five years after his death) a notarized deed, referring to the movement begun by the Guzzolini, denotes it as the « Order of Saint Sylvester ».

Pope Callistus III with two Bulls, dated 31 January 1456, assigned to the Prior General Stephen of Anthony from Castelletta the income from tax on all contracts of the « Comune » (City Council) of Fabriano and also the ownership of some lands, for the restoration of the monastery of Montefano, where the body of « Blessed Sylvester » lay. In the second document, moreover, the cypress coffin containing the bones of « Saint Sylvester » is mentioned.

Two papal privileges, one by Pius II (1461) and the other by Sixtus IV (1472), grant indulgences to those who contribute towards the restoration of the church of St. Benedict of Montefano, where the body of « Blessed Sylvester » was preserved. The same appellative is attributed to Sylvester by Pope Paul III in a Bull of 1544.

In 1598 the name of Sylvester was inserted in the Roman Martyrology the 26 November (« Apud Fabrianum in Piceno, beati Silvestri abbatis, institutoris Congregationis monachorum Silvestrinorum ») and proper readings for the office of the Saint were approved.

In 1602 for the first time a monastery of the order was placed under the title of St. Sylvester, at Nepi in the region of Lazio.

The Bull Sanctorum virorum by Paul V, dated 23 September 1617, begins with an eulogy of « Saint noble Sylvester Guzzolini, a noble man of Osimo, founder of the Congregation of the Sylvestrine monks, renowned for virtue and miracles, enriched by God with great spiritual gifts, favoured with the privilege of receiving communion from the hands of the Blessed Virgin », The same pontiff inserted the name of Sylvester, with the title of « Saint » in the monastic Breviary and Missal.

The Mass and Office of the Saint were extended to the Diocese of Camerino in 1728, to all the Marche in 1729, to all the Papal States in 1779, and to the entire Church in 1890 with the insertion of the Memorial in the universal calendar (28).

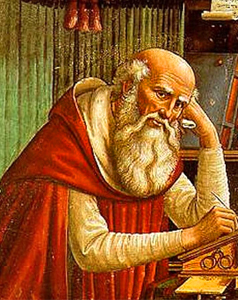

V. Iconography

Representations of St. Sylvester began in the 13th century. Their diffusion was linked to the expansion of the monastic movement founded by him, and was, therefore, specially concentrated for many centuries in the Marche, Umbria, Lazio and, in part, in Toscana.

The iconographical type of St. Sylvester underwent through the centuries very few changes; these regarded above all the age of the Saint and the colour of his habit: the latter varied according to the relative prescriptions in the Congregation at the time the representation was made.

Substantially it is a rather stable typology, while a greater variety is found in the choice of episodes in the various cycles dedicated to the life of the Saint.

The oldest representation of St. Sylvester is probably to be seen in the vast and complex decorative programme of the Fontana Maggiore in Perugia (1277-1278). One of the sculptured pieces at the edge of the upper basin of the fountain represents St. Sylvester who, kneeling, receives from St. Benedict the Rule.

Another important painting of St. Sylvester is found on a panel of a polyptych preserved the Metropolitan Museum of in New York. The work, datable to the third decade of the 14th century, is signed by Segna of Bonaventura, an artist from Siena, active in the studio of Duccio of Boninsegna. The Saint (on the right of polyptych, while on the left is St. Benedict and in the centre the Virgin with the Child) is represented in the act of blessing with his right hand, while holding in his left a book which is closed. He is wearing a grey (de gattinello) cowl, and is distinguished from the patriarch of Norcia by the younger look and the lack of a beard (29).

Also without beard is the St. Sylvester depicted in a polyptych by Fiorenzo of Lawrence, found in the National Gallery of Umbria in Perugia. It was painted between 1487 and 1493 for the Sylvestrine church of St. Maria Nuova (Perugia), now of the Servites. The Saint is wearing a beige cowl and is holding a closed book in his hand.

Worthy of note is also a fresco by Anthony from Fabriano (end of the 15th century, perhaps 1474), found in the parish church of La Castelletta, 2 km from Grottafucile. St. Sylvester is painted without beard, seated on a throne, his right hand raised in blessing, while in his left hand he holds an open book.

Later the Saint is represented with beard and advanced in age. This is the case of the painting preserved in the archives of Montefano (probably dating from the end of 15th century). Here Sylvester, wearing a tan cowl, holds a cross in his right hand and the Rule of St. Benedict in his left.

Interesting iconographical elements regarding St. Sylvester are found St. Benedict’s church in Fabriano. To be specially noted is a narrative cycle regarding the life of the Saint. It was painted by Simon de Magistris from Caldarola towards the end of the 16th century. It consists of nine mural frescos, which are now partly ruined by humidity. The Saint is always represented with beard, elderly, and wearing a tan cowl. In the painting of the Virgin who saves St. Sylvester we see for the first time, the abbatial mitre and crozier.

Starting from the 17th century the iconographic theme of the communion received at the hands of the Virgin, becomes prevalent till today. The oldest painting of the « Virgin giving St. Sylvester the Eucharist » is to be found at Montefano. The work can be dated to 1632 and is attributed to Claudio Ridolfi, a painter from Verona, who worked for a long time in the Marche. The Saint with beard wears a tan cowl; an angel holds the croziers while on the ground are the mitre and the book of the Rule.

In one of the codices of the archives of Montefano there is a beautiful miniature of the Saint dated from 1657. He is represented with beard, tan cowl, mitre and crozier, in the act of adoring the Cross which is being presented to him by an angel. In the background one can see the monastery of Montefano with its architectural structure of the 16th century.

Interesting is also the cycle of paintings of the « Saint’s Story » found in the monastery of Montefano. It contains the largest number of representations regarding St. Sylvester: twenty lunettes adorning the main cloister. The work is by Anthony Ungarini, a painter from Fabriano (second half of the 18th century. Episodes and miracles from the life of St. Sylvester are reproduced in a descriptive and popular manner with a marked preference for the anecdotal side of the human and religious vicissitudes of the Saint (30).

The Sylvestrine Congregation

I. History – II. Legislation and government – III. Spirituality – IV. Habit – V. Coat-of-arms – VI. Noteworthy members – VII. Superiors General – VIII. Monasteries IX. Privilegium Confirmationis

I. History

-

The period of the founder (1228-1267)

The Sylvestrine Congregation was founded by Sylvester Guzzolini (1177-1267), in the Marca of Ancona, in a period – the thirteenth century – which saw the progressive, even though contested, consolidation of papal power in the region. Possession of the Marche was very important for the Church, because they separated the territories of the Kingdom of Sicily from those of the Holy Roman Empire, – the two crowns having been united by the Emperor Henry VI (1190-1197) – and thus constituted a barrier crucial to the survival of the pope’s temporal dominions. In the struggle between papacy and empire, the « Comuni » (cities) of the Marca were allied sometimes with one side and sometimes with the other depending on the circumstances at the time (1).

About 1228 the hermit Sylvester received his first disciples at Grottafucile, and they became the nucleus of the new order. It was the very year in which the troops of Emperor Frederick II, under the command of Rinaldo the duke of Spoleto, invaded the Marca. Only two years later, in 1230, the region was again under the rule of Pope Gregory IX and was governed with a certain stability by a rector nominated directly by the pontiff.

In 1231, the first definite date we have in the history of the Congregation, Sylvester founded the hermitage of Montefano, near Fabriano (then in the diocese of Camerino). His movement was centered here and obtained canonical approval from Innocent IV on the 27 June 1248 with the Bull Religiosam vitam (2). The privilegium confirmationis of the « Order of St. Benedict of Montefano » was sent from Lyon, where the pope had sought refuge from the war with Frederik II who, in 1239, had again occupied the Marche and, in 1241, had arrived with his army at the gates of Rome. Fabriano, like other cities of the Marche, had passed over to Frederick II, becoming one of the major supporters of the imperial idea. In 1248 the emperor’s army controlled almost the entire region, in spite of the fact that Frederick had been excommunicated by the first Council of Lyon (1245) and the faithful prohibited from obeying him. After his death, which occurred in 1250, all the cities of the Marche returned to the control of the Church. The following year Innocent IV came back to Italy.

In founding the hermitage of Montefano, Sylvester was helped by the Canons of St. Venanzo, the mother church of Fabriano (3). They continued to show their friendship and esteem by inviting him « very often » to their church that he might « proclaim word of God to the people » (Life, ch. 30 Engl. – ch. 27 Lat.).

It seems that the first monks at Montefano won almost immediate favour with the local population because of the great austerity of their lives. The « Commune » (city Council) as well as private citizens were generous in giving the monks of « Brother Sylvester » gifts and land (which included money, land, houses, and donkeys) (4). In 1265 Guido, the bishop of Camerino, granted a 40 days indulgence to members of the faithful who visited the church of Montefano with devotion between the feast of St. Benedict (21 March) and the octave of the feast of the apostles James and Philip (8 May), leaving alms and offerings to support the monks.

Thus, in this rather haphazard way, Montefano gradually consolidated its economic position. Moreover, even in a period of political and religious turmoil, the support of the local civil and ecclesiastical authorities, gave the monks the necessary independence to develop a normal community life.

In 1255 the first General Chapter (that we know of) was held at Grottafucile. The members were: Brother Sylvester, Prior of the hermitage of Montefano, the Priors of St. Peter of Osimo, St. Bonfil of Cingoli, St. Mary of Grottafucile, St. Bartolo of Serra San Quirico, St. Mark of Ripalta and 19 monks (5).

In 1264 the rector of the Marca of Ancona allowed the monks of the « Order of Brother Sylvester, who lived according to the Rule of St. Benedict » to build churches, with the permission of the diocesan bishops, to preach and to administer the sacraments (6).

-

From the death of the founder to the « Commendam » (1267-1325)

At the death of the founder, on 26 November 1267, the two vicars of the Order, Bartolo from Cingoli and Joseph degli Atti from Serra San Quirico, notified all the communities of the death of « Brother Sylvester, Prior General of the hermitage and of the Order of Montefano » and convoked the General Chapter for the 1st January 1268, in order to elect the new « shepherd » (7).

There were twelve monasteries at that time, all situated within the Papal States: – in the Marche:

1) St. Benedict of Montefano, near Fabriano

2) St. Mary of Grottafucile

3) St. Mark of Ripalta

4) St. Bonfil of Cingoli

5) St. Bartolo of Serra San Quirico

6) St. Pietro del Monte of Osimo

7) St. Thomas of Jesi

8) St. Bartolo of Rocca Contrada (Arcevia today)

9) St. John of Sassoferrato- in Umbria:

10) St. Mark of Sambuco

11) St. Benedict of Perugia- in Lazio:

12) St. James in Settimiano of Rome.

Initially, therefore, the Congregation had a distinctly regional character, which it preserved for most of its history down through the centuries.

At the General Chapter, held to elect a successor to Sylvester, 82 monks participated in person and 37 by proxy: 119 in all, which was probably the total number of Sylvestrine monks at the time the founder died (8).

On 4 January 1268 Joseph degli Atti from Scrra San Quirico was elected head of the Congregation. During his brief rule (1268-1273), he was involved in a controversy with Guido, bishop of Camerino, due to the latter’s undue interference in the internal affairs of the Order.

The dispute began in October 1268 when Brother Joseph, having received faculties from the vicar of the rector of the Marca of Ancona, put into the prison at Montefano two monks: Brother Compagno chaplain to the bishop of Camerino, and Brother Gabriel, because they were found guilty of « serious transgressions » against the Rule of St. Benedict. The bishop demanded that the two monks be freed and sent to him. Because Brother Joseph opposed him, maintaining that « it is the task of the Prior to correct his own monks » the bishop prohibited burial or the administration of the sacraments to the faithful in the Sylvestrine churches situated within his diocese. He banned, as well, the monks begging, contesting the fact that the monks were « so poor – as they maintained that they could not live and serve God without the help and the alms of the faithful » the Sylvestrines, in fact, according to bishop Guido, « possessing properties, should live by the work of their hands, while the alms should be given to support those poor who do not have the possibility of cultivating their own possessions ».

The Prior General appealed first of all to the rector of the Marca, then to the Conclave of Viterbo, and finally to Pope Gregory X. The controversy was over in 1272 with the death of the bishop, even though it was concluded officially in 1285 by bishop Rambotto, successor of Guido at Camerino, with full recognition of the rights of exemption for the order of Montefano from dioccesan jurisdiction (9).

The time of Bartolo from Cingoli, the third Prior General (1273-1208) signaled the start of a profound renewal within the monastic family of Montefano. In fact, after the death of the charismatic Sylvester and the long struggle with the prelate of Camerino, the order became conscious of the need for a juridical and institutional structure which would reflect the spiritual intuition of the founder.

So that the original charism might be reflected in the governmental structure of the order, Bartolo from Cingoli entrusted to Andrew of James from Fabriano, one of the monks, the task of writing the Life of Sylvester based on the testimonies of those first disciples who were still living. In this way the authentic spirituality of the founder became the basis for the evolution of the Order.

The merit for having given juridical expression to the spiritual ideals of Sylvester goes to the fourth Prior General, Andrew of James from Fabriano (1298-1325). Indeed it is to him that we owe the promulgation of the « liber constitutionum » (The Book of the Constitutions), the oldest that we have, which fixed the identity and the style of life of the Sylvestrine movement.

The Constitutions, with the introduction of variants of no little consequence for the praxis and for the primary aim of the Congregation, show a clear break with certain ways of acting evident in the beginnings, and an adaptation to the new situation at the start of the fourteenth century (10).

Above all, there was a progressive disappearance of the eremitical character of the Order because of its increasing presence in the towns and cities (11).

The founder, who in the Life is called the « magnificent hermit » after withdrawing from Osimo retired to the solitude Grottafucile, where he had received his first disciples. These lived in separate cells, however. Moreover, Sylvester chose solitary sites for his monasteries, in preference to the cities and towns (cf. Life, preface).

The monks of those first communities were considered « hermits ». Blessed John the Solitary spent his days at Montefano (officially called a « hermitage » in the « privilegium confirmations » of Innocent IV) in a cell built in the woods, standing apart from the monastery buildings (Life, ch. 38 Engl ch. 34 Lat.). Blessed John of the Staff lived as a « recluse » in a cell on the ground floor of the monastery, which was assigned to him by the founder for health reasons. Finally, Sylvester remained bearded throughout his life (Life, ch. 16 Engl ch. 14 Lat.), a privilege traditionally reserved for hermits as a sign of their calling.

As well, the practice of begging almost ceases, as a result of Decrees coming from the Second Council of Lyon, which with the constitution Religionum diversitatem nimiam, promulgated on 17 July 1274, took up the question of the « excessive number » of religious movements inspired by evangelical poverty which had sprung up after the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. The document imposed severe limitations (e.g. prohibiting the admision of new candidates and the opening of new houses) on those orders approved after that Council, whose only means of support was begging. The Dominicans and Franciscans were excluded from the provisions.

Brother Bartolo third Prior General, and his monks », fearing that their Congregation would be confused with the mendicant Orders taken to task by the Second Council of Lyon, and « wishing to abandon the practice of begging, decided to live exclusively from their own goods, according to the spirit of the Rule of St. Benedict and the ‘privilegium confirmationis’ of the Order » (Life, ch. 48 Engl ch. 44 Lat).

Besides, the Congregation began to take on a predominantly clerical character, with the monks taking up pastoral ministry and teaching. The Constitutions promulgated by the fourth Prior General show that such a state was already advanced, since in Sylvestrine monasteries, conventual mass was celebrated every day, and twice on Sundays and on the principal Feastdays of the year. Private masses were also provided for, and could be celebrated during the conventual mass.

Besides, provision was made for a certain number of confessors within the community, as each monk had to confess himself three times a week. Finally, to cover the principal offices in the monastery (Prior, Vice-Prior, Hebdomadarian for the office and also for the Mass), it was necessary to ordain more priest-monks, and this became an increasing trend, which became more and more a distinctive sign amongst the monks.

In 1296 the Sylvestrines took possession of the church of St. Maria Nuova, in Perugia, and a parish came with it (12). It was the first entrusted to the Congregation. During the rule of Andrew of James from Fabriano (1298-1325), diocesan bishops gave parochial jurisdiction to the Sylvestrine churches of St. Mark of Florence (1 July 1300) and St. Benedict of Fabriano (4 July 1323). In the following centuries these pastoral activities became more and more intense.

The urbanization of the communities favoured, also, a growing involvement in the general civil and ecclesiastical life of the time (13).

Geographical expansion, growth in numbers and spiritual vitality characterize the close of the thirteenth and the beginning of the fourteenth century.

The following monasteries were opened (14): – in the Marche:

St. Lucy of Serra San Quirico (1276)

St. Maria Nuova of Matelica (1288)

St. Mary of Belforte (1291)

St. Martin of Bura, near Tolentino (1295)

St. Nicolo of Tolentino (before 1298)

St. Maria di Piazza of Recanati (1326)

St. Benedict of Cingoli (1327)

St. Anthony of Camerino (1330) – in Toscana:

St. Mark of Florence (1299)

Holy Spirit of Siena (1311)

St. Nicolo of Montepulciano (1332)

St. John the Baptist of Montepulciano (about 1332) – in Umbria:

St. Gregory of Salto, near Orvieto (before 1287)

St. Maria Nuova of Perugia (1296)

St. Angel of Casacastalda (1302)

St. Maria Novella of Orvieto (before 1322) – in Lazio:

St. Pietro della Castagna of Viterbo (1280)

St. Mary of Bagnoregio (before 1298)

St. Mary of Fiano Romano (before 1298).

The Sylvestrines reached almost two hundred members, a limit they have never passed in more than seven hundred years of history (15). Only recently have the numbers of members of the Congregation returned to those of the beginnings. In the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries the vita silvestri (Life of Sylvester), the vita Iohannis a Baculo (Life of John of the Staff) and the Vita Hugonis (Life of Hugo), two of the first monks, were edited, according to the rules of medieval agiography. The (Vita Bonfilii Life of Bonfil) was also copied, being attributed by the tradition to founder himself (16).

During the long term of office of the fourth Prior General, Andrew of James from Fabriano (17), the Congregation found itself involved in the struggle between the Guelphs (supporters of the Pope) and the Ghibellines (followers of the Emperor).

At the beginning of 1316, under the leadership of two brothers, Lippaccio and Andrew Guzzolini, who were, according to a family tradition, nephews of the founder, the « Comuni » (cities) of Osimo and Recanati rebelled against papal rule. In December of the same year a Ghibelline force, led by Frederick of Montefeltro, attacked and plundered Macerata, the seat of the rector of the Marca of Ancona. An army was immediately raised the by papal authorities, made up of contingents of troops taken from the cities which remained faithful. Since the city of Fabriano refused to send the required forces, it was placed under interdict, which, however, was not respected by most of the clergy. The rebels were heavily fined, deprived of ecclesiastical benefices, and denied offices and titles for life. Amongst those condemned by the rector Amelius of Lautrec in a document dated the 17 March 1320 were: the Prior and Canons of St. Venanzo Andrew of James « Prior General of the order of St. Benedict of Montefano&g »; Brother Dionysius, « Prior of St. Benedict of Fabriano »; Crescenzio Chiavelli, Abbot of St. Vittore delle Chiuse, who had been a Sylvestrine monk: the Abbot of Valdicastro, where the body St. Romuald was. Brother Sylvester, monk of the order of Montefano, was given the task of asking the general absolution for the clergy of Fabriano, which was granted on 15 March 1322 following the payment of 78 gold florins (18)

-

The period of the Commendam (1325-1544)

On 20 November 1325 Pope John XXII, suspending the normal procedure by which the Prior General was elected by the monks in the General Chapter, chose Matthew from Esanatoglia for this office, thus beginning a sequence of thirteen appointed Priors General (1325-1544), nominated directly by the Holy See. As to chancery rights and tax on the benefice received, the Priors General « in commendam » corresponded to the Apostolic Camera the sum of 63 gold florins, to be paid in cash or by instalment (19).

During the period of Matthew from Esanatogia Prior General (1325-1331), the struggle between the Guelphs and Ghibellines became more acute following a serious conflict between Pope John XXII and the Emperor Ludwig of Bavaria. The latter arrived in Italy in 1327, supported by the Ghibellines. He had declared the Pope deposed, since he lived at Avignon instead of Rome – the papal seat – and had appointed as his successor, the anti-pope Peter Rainalducci from Corvaro, a Franciscan, who took the name of Nicolo V (12 May 1328).

In his march towards Rome Ludwig passed through Viterbo, and was received enthusiastically by his followers. Brother Isaiah from Tolentino, a Sylvestrine monk from the community of Fiano Romano, dared under these circumstances to publicly celebrate mass and declare his support for Ludwig. He was declared a heretic by John XXII, but was granted absolution on 20 April 1328, being banned from public office within the Congregation for a year, forbidden to leave the monastery for a month and obliged to fast on bread and water once a week for an entire year.

The anti-pope Nicolo V, with a Bull dated 5 November 1328, elevated Fabriano, which had taken the side of the Emperor, to a Diocese, appointing Morico, Abbot of St. Biagio in Caprile, the first bishop. He deposed Matthew from Esanatoglia Prior General of the order of St. Benedict of Montefano, for supporting the heretic James from Cahors (i.e. John XXII); and decreed that the goods of Montefano and Valdicastro were to form the means of support for the new bishop.

Nicolo V abdicated in 1330, having been abandoned by Ludwig, and in the following year part of the papal territories returned to the control of John XXII. The rector of the Marca of Ancon on 14 August 1331, published the sentence of absolution for the clergy of Fabriano who had supported the Emperor and the anti pope, imposing on them abstinence from meat and wine for three years, a pilgrimage to the tombs of the Apostles in Rome and commuted to the recitation of the penitential psalms and the litany. 23 Sylvestrine monks took advantage of this pardon (20).

The Commendam (21), together with the political instability of the Papal States, pestilence (22), famine and earthquakes, were the principal causes of the economic and numerical crisis the Order suffered in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Besides the fall in the number of monks, which made regular observance difficult in many monasteries, documents of the time emphasise grave internal difficulties, certainly the most serious in the history of the Congregation, which are evidence of the crisis Sylvestrines went through during this period.

In 1362 the community of St. Mark of Florence rebelled against the authority of the Prior General, Nicolo from Cingoli, maintaining: that he had obtained surreptitiously the papal Bull nominating him; that he had not sworn loyalty to the Holy See as required by Canon Law; that he had forced obedience from the priors and the monks with the threat of imprisonment; that he lived a dissipated life as if he were a great lord. The insubordination stopped only when the Prior General put all the monks concerned in gaol, depriving them of « all they had for their use » (23).

With the appearance of factions within the Congregation resulting from a crisis of authority, as for example occurred at the General Chapter of 1368 with the election of two Priors General Pope Urban V declared both elections invalid, because the vacant benefices were reserved to the Holy See), many monks left. The Prior General, John from Sassoferrato, obtained from Urban V the faculty to capture and imprison the « apostates » (Bull of 10 December 1368), and to ban them from entering other monasteries with the exception of the Carthusians, Monte Oliveto and the Sacro Speco of Subiaco, considered stricter than the Sylvestrines (24)

In 1378, with the election of the anti-pope Clement VII (1378-1394) by thirteen cardinals opposed to Urban VI (1378-1389) the great schism in the West began, finishing only in 1417. This brought about serious damage to the papacy and church life, because it involved various countries, certainly in Italy, and particularly in the Papal States, where the struggle between warring factions brought complete anarchy.

Sylvestrine monasteries, situated mainly in the Papal States and in cities at war with one another, felt the effects of this. The consequent isolation of the houses had negative effects: General Chapters and Visitations, the normal means of watching over the spiritual and economic lives of the monks as well as the discipline of the communities, became rare and ineffective. In particular General Chapters were not really representative as monks had difficulty travelling on account of the warfare.

In 1383, because of the troubled times faced by the Congregation, the Prior General John from Sassoferrato began serious discussions on union with the Celestines. These came to nothing, principally because of the strong opposition of the communities of St. Mark of Florence and of Holy Spirit of Siena. On 12 June 1385, the Prior General, on visitation to the Florentine monastery, in order to gain « obedience and respect » from the eighteen monks of the community, was forced to swear on the Gospels that he would not, in the future, consent to a union of the Congregation with other orders (25).

Towards the end of the century, besides, the Prior General was transferred from Montefano, a place no longer safe because of roaming bands of political exiles from Fabriano, the monastery of St. Benedict in the city itself (26).

A deed of 1391 is the first witness we have for the existence of a Cardinal Protector for the Sylvestrine Congregation, whose principal tasks were the defense of the Congregation against its opponents, surveillance to insure orthodoxy and fidelity of the order to the Church, and to see to the observance of the Rule and the Constitutions. In the course of the centuries, the excessive interference of the Cardinal Protector in the internal affairs of the Congregation, as was the case with many other religious institutes, provoked disturbances and unrest amongst the monks, at times.

The practice of appointed Superiors (the Commendam) of individual monasteries, for the most part relatives of the Popes, began towards the end of the fourteenth century, and is the most significant feature of the Congregation’s history in the fifteenth century. The attempts of the Priors General to rescue these monasteries were to no avail.

Another major event in the life of the Sylvestrines in the fifteenth century, without doubt, was the expulsion of the order from the monastery of St. Mark of Florence, decreed by Pope Eugene IV in 1436, to the advantage of the Dominican Friars from St. Dominic’s Convent of Fiesole. The monks, in the person of Stephen of Anthony from Castelletta, Vicar of the Onder, appealed in 1432 to the Council of Basel (which claimed to be a General Council of the Church). The Council, with a Bull dated 26 May 1436, annulled the decree of the Pope. Eugene IV then, deprived the Sylvestrines of the monastery of the Holy Spirit of Siena, as well, which was then given to the Congregation of Santa Giustina in 1437 (27). The polyptych of Segna of Bonaventura, depicting the Blessed Virgin with Saints Benedict and Sylvester, now held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, came from here.

The Prior General who distinguished himself above all during this period was Stephen of Anthony from Castelletta (1439-1471) a master of Theology, who undertook a programme to reform the spiritual and cultural life of the Congregation (28). He called the attention of all the monks to Montefano « head and mother » of the Order, spiritual centre and point of reference for rediscovering the identity and original ideal, incarnated in the founder, who had wanted the monks « in the forest » that is, in solitude. According to the Sylvestrine historian, Stephen Moronti, the loss of the monasteries in the principal cities of Italy, such as Florence and Siena, did not represent anything but a healthy return to the authenticity of the beginnings.

In 1443, Stephen of Anthony obtained from Pope Eugene IV the Abbey of St. Biagio in Caprile with all its property and income, in order to restore the buildings at Montefano, which were by now falling into disrepair, and without a resident community (in 1461 the presence of one monk is recorded – the « hermit » Sylvester of James from Venice – who looked after the tomb of the founder) (29). Pope Callistus III, who had been a guest of the monks at Montefano and Fabriano from the time he was a cleric, in 1456 gave to Stephen also the property of Chiavelli (30), situated near the castle of Precicchie, as well as the proceeds of a tax he placed on all the contracts of the « Comune » (city council) of Fabriano. Finally, Pope Pius II (in 1461) and Paul II (in 1465) and six cardinals, amongst them the celebrated Bessarion (1463), increased the indulgences granted to those who visited the church at Montefano and who contributed to its restoration either with their work or by their pious alms.

In this way Montefano was repaired and to some degree its role was restored, even if in the second half of the fifteenth century and for all the sixteenth, only a small community lived there (from 2 to 4 monks).

After the last commended Prior General, Gentile Favorino Cima from Camerino, a secular priest, was murdered by a farmer of Belvedere near the Abbey St. Biagio in Caprile, Pope of Paul III, who had been the Cardinal Protector of the Congregation, decreed in 1544 that the election of the Prior General no longer for life, but for three years – should return to the monks gathered together at the General Chapter, and without outside interference. Thus every commendatory right to the « Priory of Montefano » was abolished.

-

The Sixteenth Century

On 15 October 1554 the civil and religious authorities of Fabriano, with the bishop of Camerino, Berard Bongiovanni, as their leader, occupied the monastery of St. Benedict under the pretext that the monks were not following the regular observance, and chased out the Prior General Anthony Andri and the other monks. These sought refuge at Sassoferrato, taking with them only the clothes they were wearing and a few personal possessions. The true reason, however, for the expulsion was to use the Sylvestrine monastery and its income for the erection of a new diocese. The monks were able to return on 11 June 1555 by order of Pope Paul IV, who insisted that they undergo a severe reform (31).

On 17 November 1555 the Cardinal Protector Tiberius Crispi, with the permission of Paul IV and the consent of Ignatius of Loyola, appointed Niccolo Bobadilla, one of Loyola’s first companions, « General Commissioner, reformer and head of all the Order of Sylvestrines and the nuns subject to them (32), with full faculties to visit each and every monastery of the said Congregation ».

Between 2 January and 21 March 1556 Bobadilla visited the monasteries, finding there « much less irregularity than the world believed ». The sources do not indicate any decrees for reform coming from the Jesuit, but he did make provisions to remedy abuses here and there (there is, for example, record of a monk being put into prison on Bobadilla’s orders). He gave to the Holy See a « very good report on the monks ». In fact, according to a chronicler of the time only a few individual monks had created « scandals » and had transgressed the holy institutes of our holy fathers Benedict and Sylvester (33).

Because of the renewed fervour resulting from the visitation of Bobadilla (who wrote to James Lainez, General of the Company of Jesus, in a letter dated 26 October 1557 maintaining that the Sylvestrines « have such good reputation, that the reform undertaken with them is the work of God »), some of the monks, wishing to return to the spirituality of the origins, retired to a heremitical life at Grottafucile and at St. Bartolo of Serra San Quirico (34).

In 1561, according to the oldest « tabula familiarum » (that is, list of monks and monasteries), wich has come down to us, there were 25 monasteries and 70 monks: 21 of these monasteries had less than 4 monks.

From 1565 until the early sixteen hundreds it seems there was contact between the Sylvestrine Congregation and Portuguese monasticism (and from 1581 also Brasilian), but so far it has not been possible to establish the modality and strength of such contacts (35).

Pope Sixtus V, with the letter Cum inter caeteras (7 October 1586), entrusted the Dominican Timothy Bottoni with the task of reforming the « Sylvestrine monks, in whose monasteries regular observance has fallen away ». This provision was part of the wider Tridentine programme for the reform of religious life following the Council of Trent and carried out with both energy and severity by Sixtus V during his pontificate, in the wake of the reformer popes of the second half of the 16th century.

At a General Chapter (Fabriano, 17 November 1586) Bottoni issued 26 « orders regarding the reform of all the Sylvestrine Order »: he recommended that the monks participate the Divine Office in both day and night, ordering the superiors to punish rigorously the « lazy » and « negligent » he exhorted the « priest-monks » to celebrate mass as often as possible, while he insisted that the « clerics » and « conversi » (lay-brothers) must go to confession at least once a week and to receive « the most holy sacrament of the Eucharist at least once a month »; he abrogated the practice of private savings (at that time there was the widespread practice amongst religious of having personal property): he recommended the integral practice of « fasting » and « abstinence » in conformity with the Rule and with the « oldest Constitutions »; he imposed the use of the monastic habit, which had been abandoned at the time of the Commendam for that of the secular priests; he prohibited the monks from having « long hair » and « beards »; he decreed the closure of small monasteries with one or two monks and ordered communities to be made up of at least ten religous; a smaller number would not have guaranteed the carrying of the common acts, and, above all, would not have made possible a worthy celebration of the Liturgy. The parishes linked to small monasteries had to be handed over to the diocesan clergy.

Bottoni, as well, abolished the office of the « Visitors », because the Congregation « through lack of monasteries and monks », could « be easily visited » by the Prior General, on whom he imposed the obligation to visit each community twice a year.

He also ordered that the old Latin Constitutions of the 14th century should be printed as soon as possible, translated into Italian, so that they could be « read » and « observed » by all the monks of the order (36).

The Prior General, Bonfil Fancelli, and the other monks of the Congregation (76 priests and clerics, 44 lay-brothers: 120 in all) began wearing the habit again in January 1587 (consisting of: cocolla for the clerics; hood and scapular for the lay-brothers), and renewed their vows. This was the first act of the reform, which marked the beginning of a progressive spiritual, cultural and even economic renewal at the heart of the order of Montefano.

Between 1584 and 1602 three monasteries were opened at Nepi in the province of Viterbo (Lazio): St. George, St. Maria dell’Immagine, and St. Sylvester, which was the first foundation named after the founder (37).

-

The Seventeenth Century

The first half of the sixteen hundreds was characterized by a notable expansion both geographically and numerically: there were 29 monasteries and 164 monks. The suppression of the small houses (with less than six religious) decreed by Pope Innocent X, there in 1652, was a real blow to the Sylvestrine Congregation: there resulted forced closure of no less than fifteen houses, whose the property, for the most part, was taken over by the diocesan bishops (38).

In 1660, the monastery of St. Anthony at Pescina in Abruzo Kingdom of Naples) was founded (39).

Another serious test the Congregation faced was in 1662, when Pope Alexander VII forced it into union with the Vallombrosans (29 March 1662). The new Congregation (« The Vallombrosan and new Sylvestrine Congregation of the order of St. Benedict ») was divided into three observances: that of St. Benedict, that of St. John Gualberto and that of St. Sylvester. The first two were made up of Vallombrosan monks (273 in 18 monasteries), the other one was Sylvestrine (134 monks in 15 monasteries). The coats-of-arms of the two Congregations were even united, and all the monks wore the same habit.

The Abbot General of the Vallombrosans, Daniel Sersale, was named the first Abbot General of the union, while the Abbot General of the Sylvestrines, Eusebius Ubaldi, was made the Vicar General. Later the Abbot General was to be elected in turn from each of the three observances.

The title of Abbot for the Superior General of the Sylvestrines, in place of that of Prior, was first introduced in 1610; from 1660 local superiors were given the same title.

In the first General Chapter of the new order, held in Rome at the Vallombrosan monastery of St. Prassede (26 April-8 May 1665), the Vallombrosan Ascanio Tamburini was elected Abbot General, while the Sylvestrine, Sylvester Gionantoni, became Vicar. At the unexpected death of Tamburini, which occurred on 7 June 1666, Gionantoni became Abbot, moving from Fabriano to Toscana and setting up residence in the monastery of St. Bartholomew of Ripoli, near Florence, home to the Vallombrosan Abbots General.

In the second General Chapter, held again at St. Prasede (1- 4 March 1667), the Vallombrosan Camillus della Torre, was elected Abbot General, and was immediately hostile towards the Sylvestrines. Alexander VII died on 22 May 1667, and his successor Clement IX on the 24 October of the same year declared the union dissolved (40).

-

The Eighteenth Century

No new monastery was opened in the 18th century. The missionary initiative of Joseph Marziali in Indochina (South Vietnam), from 1732 to 1740, was of passing value, but preluded that of the 19th century in Sri Lanka (then: Ceylon), and those of the 20th in USA, Australia, and India.

The number of monks fell from 145 (94 priests, 8 professed students, 3 novices, 35 lay-brothers, and 5 oblates) in 1700, to 122 (60 priests, 15 professed students, 3 novices, 34 lay-brothers, and 10 oblates) in 1797. Frequent famine and the epidemics which affected Central Italy of that period did not help (in the six-year period 1778-1783, 24 Sylvestrine monks died from « malignant fever »). The number of monasteries fell from 15 to 14 with the closure, in 1792, of St. Anthony of Pescina.

The reasons for the lack of expansion are to be sought in the precarious economic situation of the Congregation at the time, and on the limits placed on religious orders by the Holy See with respect to accepting novices. These limits were aimed at reducing the numbers of monasteries and convents, which were disproportionately high, given the size and demographic composition of the territory. In 1754, for example, Fabriano had a population of 6,000 with 21 religious houses (12 for men and 9 for women).

The Economy of the Marca Ancona, where ten Sylvestrine monasteries were situated, was severely tested by the passage or occupation by foreign troops, because of the « Wars of Succession », in which Papal States were involved during the first part of the century. The region was also hard hit by famine (particularly hard was that from 1763 to 1766) and agricultural crises: the Sylvestrine communities of Cingoli, Osimo, Sassoferrato, Montefano, Serra San Quirico, and Fabriano more than once complained of « very low harvests » throughout the century. Earthquakes also hit the area: especially serious was that of 24 April 1741, which caused much damage to the Sylvestrine houses, particularly in the Marche. The repairs were very expensive which tested the communities severely (41).

The constitutional structure of the Congregation lost much of its simplicity. Following contemporary trends, it became more centralized and complex, than it had been previously.

The wide powers which the Constitutions gave to the Abbot General and to the four Definitors (the composition of communities, the nomination of the Procurator General, of the ruling and titular Abbots, the Priors, the Bursars, the Lectors), were often the cause of differences and divisions between the active members of General Chapters.

Irregularities in the election and conduct of the Chapter of 1740, in which two parties had formed, led the losing side to appeal to the Holy See. Benedict XIV ordered an apostolic visitation, nominating Cardinal Francis Borghese, Protector of the Congregation, as Visitor.

In the report he sent to the Pope in 1741 at the end of the Visitation, Borghese lamented the lack of order, and abuses in government and economic management, although he admitted that the observance in « matters spiritual » was substantially good.

In the 18th century a special concern for the formation of novices and professed students is to be noted: decrees coming from the Chapters and Diets in this regard are both precise and detailed.

The century closed with the occupation of the Papal States by French troops, with the proclamation of the first Roman Republic (1798-1799), and with the imprisonment of Pius VI at Valencia, where he died on 29 August 1799.

The monasteries did not remain untouched by the new ideas of political liberalism coming from France. In May 1799 the Sylvestrine Bonfil Campelli, dazzled by a love of « liberty », left the monastery of St. Benedict of Cingoli to enlist in the French army at Ancona.

The « pillage of the city of Fabriano at the hands of the French troops on 28 June 1799 » impeded the convocation of the General Chapter of 1800, which was delayed until 1803.

For the Sylvestrine Congregation a new chapter in its history was open – that of the suppressions – which broke a monastic tradition of almost six centuries.

-

The Nineteenth Century

Soon after tranquility was restored with the election of Pope Pius VII at Venice (14 March 1800), and his return to Rome (3 July 1800), the fourteen monasteries of the Congregation were hit by the Napoleonic suppression.

In 1810 a Sylvestrines had to leave their monasteries. They had to abandon the habit and anything which might have distinguished them as monks; they could take with them only those things of strictly personal use, including beds, tables and chairs. An annual pension of 539 lire was given to the priests and 346.5 lire to the lay-brothers. The goods and property of the monasteries (pictures, works of art, library, archives, houses, land etc….) were itemized and sequestered. Only parish churches were spared (St. Benedict of Fabriano, St. Fortunato of Perugia, St. Lucy of Serra San Quirico, and Santo Stefano del Cacco of Rome), but most of the vestments and above all items of gold and silver were taken (42).

The Vicar General, Joachim Baroncini, had to provide for the upkeep of the church of St. Sylvester at the hermitage of Fabriano, mother and centre of the Congregation, with his only pension.

He was the « custodian » of the of Montefano sanctuary for the whole period of the suppression (43). With the restoration of the Papal States, permission for the re-opening of eight houses was granted by the Holy See. They were:

-Lazio: Santo Stefano del Cacco of Rome (1814)

-Umbria: St. Fortunato of Perugia (1814)

-Marche: St. Sylvester of Montefano (1820)

St. Benedict of Fabriano (1820

St. Sylvester of Osimo (1820)

St. Lucy of Serra San Quirico (1820)

St. Anthony of Camerino (1820 – suppressed by the Holy See in 1837)

St. Maria Nuova of Matelica (1821- left in 1842)

In 1821 the monastery of St. Mary of Sasoferrato was acquired. It had belonged to the Augustinians.

The first General Chapter after the Napoleonic suppression was celebrated at the monastery of St. Benedict of Fabriano in 1824. The monks who had returned to the cloisters numbered 41 (20 priests and 21 lay-brothers).

The novitiate was re-opened at Montefano 1825, but the following year Leo XII forbade the acceptance of new vocations, and he tried in vain to force the Sylvestrines, the Olivetans and the Camaldolese to become part of the Cassinese Congregation. It was later Camaldolese Congregation that attempted, in the person of Cardinal Placido Zurla, O.S.B. of Camaldoli, Apostolic Visitor to the Sylvestrines, to absorb the orders of Montefano and Monte Oliveto. Only the direct intervention of the following Pope, Pius VIII, in 1830, avoided the danger.

Again as a result of the low number, Gregory XVI called together a special commission of Cardinals to decide on the fate of the Sylvestrine Congregation in 1837: their opinion was favourable, and the Pontiff too pronounced himself in favour of its survival.

In April 1837, the second General Chapter after the restoration was held and it was decided to draw up a new text of Constitutions adapted to the new situation. The Sylvestrine family, at that stage, was made up of 49 monks (24 priests, 21 lay-brothers stage, and 4 students).

In 1842 the monastery of St. Theresa was opened in Matelica, province of Macerata, Marche (44).

In 1845 the order of Montefano, restricted to Central Italy hitherto, began a process of foreign expansion with the opening of a mission in Ceylon (today Sri Lanka). It was the work of the monk Joseph Bravi, and led, in the twentieth century, to the Congregation becoming international (45).

In 1860-1861 the monasteries of Umbria and Marche were subject to the laws of suppression of the Kingdom of Italy (46). A government commission was sent to every community to take possession of all goods and property and to see to the expulsion of all religious. These communities, following the directions of the Holy See, were to accept the notifications to hand over, sign the pension certificates, and then make ritual protest by declaring that they would obey only under the threat of violence.

On 16 March 1861 the monks were expelled from St. Benedict Fabriano: the Abbot General Adam Adami withdrew to Castellanio (Province of Ancona) « to the house of his parents » (where he died in 1889).

The Congregation in Italy at that time numbered 74 members (statistics are not yet available for Sri Lanka): 33 priests, 16 professed students (2 from Sri Lanka), 23 lay-brother, and 2 school-students (from Sri Lanka).

Montefano was temporarily saved by the actions of Emilian Miliani, who, in 1861, went personally to Turin to the King, Victor II. He took with him a petition which both the citizens Emmanuel and parish priests of Fabriano had signed, but in 1866, St. Sylvesters suffered the same fate as the other communities. As custodian of the founder’s tomb, Louis Bartoletti (a priest-monk) remained at Montefano with the oblate Lawrence Coccia (who died four years later, on 26 April 1870).

The General Chapter which was to be held in 1862, because of the developments arising out of the suppression, was adjourned, with permission from the Holy See, from one year to the other until in 1872 the Congregation for Bishops and Clerical Religious allowed the election of the Abbot General by written vote without the members coming together in Chapter. The votes were sent to the Abbot General, Adam Adami, at Castelplanio, who, in the presence of two monks, on 11 June 1872, counted them: Vincent Comeli was elected (nine monks voted), and then made his residence in Rome. From the tavola delle famiglie (list of monks and monasteries) of that year there were 50 Sylvestrine monks in Italy (35 priests and 15 lay-brothers).

In 1873 Santo Stefano del Cacco of Rome was suppressed: the monks were allowed to maintain custody of the church and « a part of the monastery » remained, in view of « international law in the light of our Foreign Mission », a right which the Abbot General Vincent Corneli was able to have recognized by the Government (from a Circular Letter of Corneli, dated 9 June 1874).

The courageous attempts of the Congregation to survive are linked, in a symptomatic way, to the issue of the novitiate. It was transferred from Montefano to Rome, in 1862. Here it was suppressed in 1870, to be reconstituted in Kandy (in what was then Ceylon), in 1875, and returned to Montefano in 1881.

In 1873 Montefano was put up for auction at Ancona; Tobias Lorenzetti, brother of the ex-Abbot of Montefano Lawrence Benedict Lorenzetti, bought it for 6,250 lire, on the monks behalf. Sylvestrine monks, not only in Italy but also Sri Lanka, contributed: a testimony that Montefano was recognized by all as the spiritual centre of the Congregation.

The monastery of St. Anthony in Sri Lanka was opened in The 1874, and in 1886 it became the Episcopal Seat of the Kandy Diocese. For (1857-1972) the bishops, first of Colombo, then of Kandy and later of Badulla, were Sylvestrines. The first Sri Lankan be consecrated a bishop, Bede Beekmeyer, was also a Sylvestrine, in the early nineteen hundreds. Schools were also begun by the monks in both Colombo (St. Benedict – now run by the De la Salle Brothers) and Kandy (St. Anthony’s – still run by the monks).

From 1872, because of political developments, nineteen years passed before another General Chapter could be held. In 1891 the Congregation for Bishops and Clerical Religious, in response to a request from the monks, granted the faculty to celebrate the Chapter in the monastery of St. Sylvester near Fabriano, where the remains of the founder are held. Abbot Vincent Corneli was reelected on 3 August 1891, and died on 21 January 1892.

At the end of the century the Sylvestrines were able to « reconquer » some of the property lost during the suppression (47).

-

The Twentieth Century

The twentieth century marks the gradual revival of the order of Montefano. In 1900 the Congregation consisted of 58 members: 35 in Italy (17 priests, 5 professed students, 10 lay-brothers and 3 postulants), and 23 in Sri Lanka (1 bishop, 15 priests, 3 professed students, 3 lay-brothers, and 1 oblate). There 8 monasteries were in Italy (Montefano, St. Benedict of Fabriano, St. Theresa of Matelica, St. Lucy of Serra San Quirico, St. Maria del Piano of Sasoferrato, St. Sylvester of Osimo, St. Fortunato of Perugia and Santo Stefano del Cacco of Rome), and 1 in Sri Lanka (St. Anthony of Kandy, where 14 monks and 60 students lived).

In 1910, because of political conditions in Italy which led one to fear a new suppression, the Sylvestrines thought of opening a house in the United States. The first to depart were the monks Philip Bartoccetti and Joseph Cipolletti. They established themselves at Chicopee first, and then at Frontenac in Kansas (in 1912), where the bishop of Wichita, John Joseph Hennesy, entrusted them with the spiritual care of the Italians who were working in the coal mines.

Joined by another three monks, they moved to Detroit, Michigan, in 1928, where they founded the monastery of St. Sylvester, annexed to the parish of St. Scholastica, with its Catholic school, all of which still exist (48). In 1939, the number of Sylvestrines was nine (seven priests and two lay-brothers).

In 1951 the monastery of Holy Face was founded at Clifton, New Jersey, and in 1960 that of St. Benedict of Oxford, Michigan, which became the novitiate house. In Sri Lanka the monastery of St. Sylvester of Ampitiya (near Kandy) was opened in 1928; in 1962, that of St. Benedict of Adisham, Haputale (now in the Badulla Diocese) (49), with the novitiate in 1966, that of St. Antony of Padua, at wahacotte in the Kandy Diocese, with parish and sanctuary attached. In the last 45 years in Italy, five monasteries have been founded: St. Vincent’s at Bassano Romano (1941), Holy Face at Giulianova (1953), St. Joseph’s at Terni (1962, closed in 1977), S. Maria Mater Ecclesiae at Saluggia (1964), our Lady of Crestochowa in Rome (1974) attached to a parish.

Sylvestrines first came to Australia in 1949 in the person of Fr. Peter Farina. He had come from Sri Lanka and was entrusted with the parish of St. Gertrude at Smithfield. In 1950, in place of Farina–who was recalled to Sri Lanka–two monks arrived from USA and in the following year another two from Italy (in 1956 there were 5 monks at Smithfield: 4 priests and 1 lay-brother), who carried out much pastoral work ». In December 1957 a monastic community was begun in the monastery of « Subiaco » Tydalmere, about 10 km from Smithfield, formerly belonging to a community of Benedictine nuns, who had moved further north of Sydney. The monks ran a small primary school there for three years.

In May 1961 the monks themselves left Rydalmere and soon commenced building a monastery dedicated to St. Benedict at Arcadia–a rural zone about 25 km north-west of Sydney (50). Since 1969 they have also the pastoral care of the Catholics of the area.

In 1970 the two communities had 15 members (11 at Arcadia, 4 at Smithfield).

In 1949 tow monks from Sri Lanka, Boniface Valiaparampil and George Kuthukallunkal, went to Cochin, in the Indian state of Kerala, to begin an experiment in monastic living (51). They were later joined by others and had begun a school. In 1953, however, due to circumstances, the initiative was abandoned.

Because of a changed political situation in Sri Lanka in 1962, some monks of Indian nationality, forced to leave the island in so much as they were foreign missionaries, founded the monastery of St. Joseph at Makkiyad in Kerala (52). Later the monasteries of St. Sylvester at Bangalore in Karnataka State (1973) and Jeevan Jyoti Ashram at Shivpuri in Madhya Pradesh State in 1980 were opened (53).

On the 19 September 1973, the Congregation became a member of the Benedictine Confederation. On the 6 October 1986 there were 199 Sylvestrines: 61 in Italy (distributed throughout 5 monasteries and 3 houses), 46 in Sri Lanka (in 3 monasteries and 2 houses), 25 in USA (3 monasteries and 1 house), 16 in Australia (2 monasteries) and 51 in India (3 monasteries).

Sylvestrine monasticism which had for a long time a national, if not a regional character, is now spread throughout four continents. St. Sylvester, through the works of his sons, has lived by now, for more than 750 years of the history of the church and the world.

- Legislation and Government

- The Thirteenth Century

The fundamental characteristic of the Congregation was its centralization. The focus on Montefano and its Prior was clear from the beginning, and was expressed explicitly in the Constitutions of the fourteenth century (54).

The first juridical and organizational elements of the Congregation are contained in the document Religiosam vitam (The Privilegium confirmationis), promulgated by Innocent IV at Lyon, on 27 June 1248. The papal Bull speaks of the monasteric Order Founded in the hermitage of St. Benedict at Montefano under the Rule of St. Benedict. The monasteries called loca (places) to distinguish them from the hermitage, depended on Montefano, whose Prior was elected for life « according to the will of God and the Rule of St. Benedict ».

From documents of the thirteenth century we learn that the Orior of the hermitage of Montefano, or Prior General, was elected at the General Chapter, convoked by the Vicar of the Order. All the monks had the right to participate and to vote. If a monk could not attend, for a just reason, he could nominate a confrere as his proxy by means of an affidavit sent to the Vicars. The Prior, with the consent of the General Chapter, nominated the Vicars (two or three) who in the case of death would take up the government until a new election. The Prior would also preside at the General Chapters, and, at times, also the Conventual Chapters.

The documents which we posses do not allow us to establish the frequency, nor all the powers of the General Chapter in the thirteenth century. Besides the task of electing the Prior of the Order, it nominated the councillors or procurators to both civil and ecclesiastical authorities and courts.

-

The Constitutions of the Fourteenth Century

The oldest Sylvestrine Constitutions known to us come from the beginning of the fourteenth century and were the work of the fourth Prior General, Andrew of James from Fabiano (1298-1325). They exist in two editions, substantially the same, conserved respectively in the Württembergische Landesbibliothek in Stuttgart and in the archives at Montefano. They remained in power, with a few modifications, until 1610. The copy in Stuttgart can be dated between 1303 and 1308, and that of Montefano to the period 1311-1317 (55).